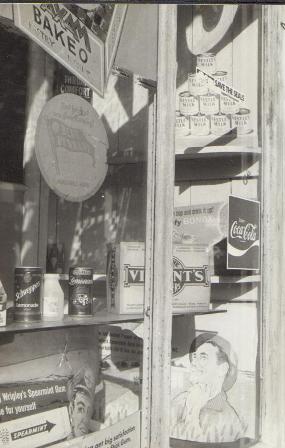

GHOST WINDOW

Anna Tambour, guest blogging

Ben Peek has been painting a brilliant picture of Sydney. But like a painting that's been painted over, there's something more going on . . .

The shop is the ground floor parlour of a typical Sydney inner-city (1880s suburban) terrace--14-foot wide; style, in admiration Mr Pooter's home, of "Diary of a Nobody" fame; dimensions, a railroad car. The house lot is 14-foot wide. It sweats in the summer, streams down the inside walls in the rain, and freezes its occupants in the winter, though the winters are mild outdoors. Air and light are alien.

Ask the old man in the shop for anything, and his answer is the same. "No. Out of it." Today he's just said no to a request for salt, from the only person who bothered to come in from the light. The only things left on his shelf are, in fact, one packet of Sao biscuits, a bleached roll of Ford Pills ("Keeping you looking trim and healthy.Keeps you really regular") and three hard boxes of Saxa salt.

His window looks obliquely at the neighbourhood tuck shop. It's almost dinner (lunch) for the rubber factory, the marble works, the paint makers. The sandwiches have just been made, enough for the rush--cheese and tomato, ham and pickle (pickle is a yellow stuff that looks like something Van Gogh used). The tuckshop woman is almost ready for the blokes to stream in through the plastic slats of her doorway. There's only one thing left to do: give the sandwiches a final go-over with a spray of Aeroguard.

The ghost window smells the flyspray wafting out of the tuck shop, just as it smells years of mutton, potatoes, and cabbage from its own owner's tea (dinner), the same day after day. The ghost window hears the trots of a summer evening--in two ways: from the radio, and travelling on the summer air, from the races only a short walk away. The ghost window watches the foot traffic on a weekend, headed for the only two places open to fill your needs--lay your bets; and buy your grog. Bread? Had to have bought it already. Workers' rights, you know.

The ghost window sees this world because it does not understand the worlds that crashed into it in the next startlingly few years. It doesn't understand the new people who came to scavenge the sites of the torn-down factories, looking for wood, which they burnt in the tiny coal fireplaces of their terraces--the terraces being renovated by owner builders, often in the secrecy of night. They'd strip their kitchen walls to expose the bricks, making the house even gloomier, but then they'd pop a skylight in, and a window that looked out on the cemented strip of "garden" out back--which had to be dealt with, too, though privacy? Where could anyone get any privacy? These people who had to pick nails out of their fire grates didn't last long, many of them. They got tired of walking around wrapped in blankets in the winter. They tired of the unfixable problems of these developer-built houses, built on rubble and of rubble; all unfixable cracks and entrenched mildew.

The ghost window watched these people, as it watches the new ones now-- the apartment dwellers--. Where the tuck shop was, a gallery sits now. The neighbourhood air is filled with new smells unidentifiable to the ghost neighbourhood.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home